AUTHOR SPOTLIGHT: Natalie Hopkinson

“Natalie Hopkinson has an established reputation as one of the most sophisticated commentators on contemporary black culture.” —Mark Anthony Neal, author of New Black Man

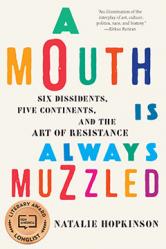

As people consider how to respond to a resurgence of racist, xenophobic populism, A Mouth Is Always Muzzled tells an extraordinary story of the ways art brings hope in perilous times. Weaving disparate topics from sugar and British colonialism to attacks on free speech and Facebook activism and traveling a jagged path across the Americas, Africa, India, and Europe, Natalie Hopkinson, former culture writer for the Washington Post and The Root, argues that art is where the future is negotiated.

Part post-colonial manifesto, part history of the British Caribbean, part exploration of art in the modern world, A Mouth Is Always Muzzled is a dazzling analysis of the insistent role of art in contemporary politics and life. In crafted, well-honed prose, Hopkinson knits narratives of culture warriors: painter Bernadette Persaud, poet Ruel Johnson, historian Walter Rodney, novelist John Berger, and provocative African American artist Kara Walker, whose homage to the sugar trade Sugar Sphinx electrified American audiences. A Mouth Is Always Muzzled is a moving meditation documenting the artistic legacy generated in response to white supremacy, brutality, domination, and oppression. In the tradition of Paul Gilroy, it is a cri de coeur for the significance of politically bold—even dangerous—art to all people and nations.

* * * * *

The New Press is excited to introduce Natalie Hopkinson, author of Go-Go Live and Deconstructing Tyrone (with Natalie Y. Moore) and the upcoming A Mouth Is Always Muzzled: Six Dissidents, Five Continents, and the Art of Resistance, available February 6. Natalie is a columnist for the Huffington Post, a fellow at the Interactivity Foundation, and an assistant professor in Howard University’s graduate program in communication. She is a former writer, editor, and culture critic at the Washington Post and The Root.

We sat down with Natalie to ask her about her new book and her thoughts on journalism and the arts in this current political climate.

Tell us about your book, A Mouth Is Always Muzzled, and how you came to write it.

NATALIE HOPKINSON (NH): The book began as a project for the Interactivity Foundation (IF), a nonprofit based in West Virginia where I am a fellow. The topic was the “Future of the Arts & Society.” I convened many, many panel discussions with artists, including one in Guyana (formerly British Guiana) when I was on an extended family visit in 2011. That was when I first connected with the young writer and activist Ruel Johnson, who won his second Guyana Prize for Literature soon after. A couple years later, Julie Enszer of The New Press approached me about developing a book-length treatment of the arts project. So I headed back to Guyana and connected with another decorated Guyanese artist, the painter and writer Bernadette Persaud.

Ruel is a millennial Afro-Guyanese man, and Bernadette is a baby boomer and Indo-Guyanese woman. They are two feisty, provocative artists who push society forward, but with radically different temperaments, approaches, and philosophies about the place of the artist in society. I followed their lives as they navigated the historic 2015 election in Guyana haunted by ghosts of slavery, indenture, colonialism, racial resentment, and oppression. The rest of the chapters and the other four artists (John Berger, Walter Rodney, Kara Walker, and Martin Carter are much better known) helped to fill out the historical pieces about how they got there and what political change might mean at this time in history. In telling the stories of these six artists, I tried to explore bigger questions . . . what are the roles of the artist in society? What part do they play in making change?

What surprised and/or delighted you during the process of writing the book?

NH: What shocked me was how brazen and entitled people in power can be in trying to dictate what artists say, and how violently they muzzle expression they don’t like. From the British, African, and Indian rule in Guyana, past and present, this is the common string. What was delightful to me is the many ways that artists with so much to lose rip off these muzzles. They do it with humor, grace, panache, and a fierceness I can only admire and appreciate.

A lot of research went into this book. What was the best part about researching A Mouth Is Always Muzzled?

NH: The best part is getting to hang out with art and artists. They are the best. I also love getting to understand history, to unfurl all of the craven dimensions of sugar in the past and its legacy today. As far as my parents’ native Guyana specifically, it was getting to understand things I took for granted my whole life. I grew up eating roti and curry (India), metemgee stew (Africa), pepperpot (indigenous South America), garlic pork (Portugal), and chow mein (China) and not realizing I was consuming all of these colonial cultural legacies the whole time. Guyana is billed as the “Land of Six Peoples” and all have left their mark, and all these people are still arguing with each other. Brackette Williams called it “war in my veins.” This explains so much about my family. You have no idea.

Who is your ideal reader?

NH: My ideal readers are the people who love art, history, and politics and enjoy seeing them as a living, breathing, contemporary thing with current dilemmas and current applications. Maybe they like to travel, experience new sounds, new voices, new flavors and colors. People who delight in finding human connections in unlikely places.

This book explores art intensively in a variety of locations. Who are three people you would like to go to a museum with and to which museum would you take this group of people?

NH: Thelma Golden, Sarah Thornton, and Edwidge Danticat. I would take them to the Castellani House in Georgetown, Guyana, a place I am certain they have never been before. It is a beautiful former residence of first the chief botanist in British Guiana colonial days, then it was the residence of Forbes Burnham, Guyana’s first leader after independence, where he kept horses, and now an art museum. I would invite Guyana’s decorated artist Bernadette Persaud along, too, so she can give them the same thrillingly politically incorrect tour she gave in my book.

What has been your experience working with The New Press?

NH: Fantastic. I am humbled to be in such great company at The New Press with so many authors I have admired. The New Press is doing so much fearless, cutting-edge work that is changing the culture and sparking important conversations that would not otherwise happen. My editor, Julie Enszer (along with my fierce mother!) has been riding shotgun on this bumpy journey. Julie believed I might have something to say about art and fought for the book when it was less clear and focused. She did not blink, and actually cheered when I delayed and radically changed directions. She is a fabulous editor, and she has become a wonderful friend.